| Gary

L. Cromwell

Department of Animal and Food Sciences

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky 40546

Introduction

Dried milk powder and dried products

originating from milk have been used in pig starter

diets for many years. These products have been shown

to enhance feed intake, growth rate, and health of newly

weaned pigs, especially those weaned at young ages.

Furthermore, the beneficial effects of dried milk and

dried milk products continue to benefit weanling pigs

for several weeks following weaning.

Milk contains many important components

that have superior nutritional value to animals. One

of these important components in milk is the carbohydrate

fraction, which is predominately the disaccharide sugar,

lactose. In addition, the individual protein fractions

of milk and the excellent profile of amino acids in

these proteins contribute to the excellent nutritional

properties of milk. The lipids (mainly butterfat) in

milk serve as a concentrated source of energy. In addition,

calcium and phosphorus are found in relatively high

concentrations in milk and they, along with other minerals

and vitamins, contribute to its nutritional value.

Dried skim milk, dried buttermilk,

and casein are examples of fractions derived from liquid

milk that can be used in animal feeds. An important

product derived from cheese production is liquid whey.

Dried whole whey powder is an excellent component for

inclusion in pig diets. Liquid whey can be subjected

to a crystallization process that yields lactose and

delactosed whey, or it can be subjected to an ultrafiltration

process which results in two end products – whey permeate

and whey protein concentrate. These various components

and fractions of the milk and cheese industries will

be addressed, but this paper will give the most attention

to dried whole whey and lactose.

Dried Products from Liquid Milk

Dried skim milk at one time was commonly

used in diets of pigs weaned at an early age. Fifty

to seventy-five years ago, pigs were routinely weaned

at 6 to 8 weeks of age. However, swine producers began

to adopt more intensive production practices in the

1960’s, and this trend necessitated earlier weaning

of pigs. Weaning pigs at 3 to 4 weeks, or earlier, became

more common. Inclusion of dried milk powder in diets

for the first week or two after early weaning was a

common practice. Although dried milk was expensive,

it was an excellent source of highly digestible nutrients

(Table 1) and was a necessary component of the diet

in order to keep early weaned pigs alive, healthy, and

growing.

Today, with improved environments and

ingredients such as dried whey, lactose, dried animal

plasma, dried blood cells, and high quality fish meal

that were not readily available during those early years,

the more expensive dried milk products are less commonly

used in today’s pig diets. In addition, the exceptionally

high cost of dried skim milk relative to the cost of

dried whey prevents the use of dried skim milk in pig

starter diets. The same can be said for dried buttermilk

and casein.

Dried Milk-Based Products from Cheese

Production

Dried Whey

Large amounts of milk are used in the production

of cheese. One of the major products resulting from

cheese production is liquid whey. Years ago, liquid

whey was considered a waste product and was disposed

by dumping it into waterways, spreading it on crop land,

or transported it to land fills. In some areas of the

world, liquid whey was, and still is, fed directly to

pigs both as a source of nutrients and as a means of

disposal, but this practice is not common in the USA.

If whey is carefully dried, it makes

an excellent ingredient for animal feeds. In fact, dried

whey is the largest milk-based feed ingredient used

in the feed and pet food industries in the USA. Approximately

one-half of the dried whey produced in the USA is used

in pig starter feeds (Halpin et al., 2000). Almost all

pig starter diets contain this important ingredient

and/or one of its major components, lactose.

Dried whey typically contains about

68% lactose and 12% protein (Table 1, NRC, 1998). The

major proteins in whey are β-lactoglobulin (56-60%),

α-lactalbumin (18-24%), bovine serum albumin (6-12%),

and immunoglobulin (6-12%) (Harper, 2000). These specific

proteins not only served as a source of amino acids,

but they also serve as a defense against microbial infections

and as a source of growth factors and modulators (Harper,

2000). Other proteins in whey that are found in lower

concentrations and that are thought to have important

biological properties include lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase,

lysozyme, casein glycomacropeptide, phosphopeptides,

and fat globule membrane proteins (Harper, 2000).

Dried whey is classified as

edible grade or feed grade depending on its bacterial

count. Most of the dried whey used in pig feeds originates

from cheddar cheese plants and it is called “sweet whey”.

Dried whey originating from cottage cheese plants is

called “acid whey” and it is less commonly used in pig

feeds. Whey can be dried by either a spraying process

or by rolling thin layers of whey on heated drums followed

by scraping the dry material from the drums. The spray-drying

process involves atomizing liquid whey into superheated

air for a short period of time, and results in a powdery

and hygroscopic product. This type of drying results

in both α- and β-lactose. Roller dried whey uses a lower

heat for a longer time; it results in a granular, non-hygroscopic

product in which all of the lactose is in the β form.

From a taste standpoint, β-lactose is sweeter than α-lactose.

1NRC (1998). NRC does not list

levels of magnesium, sulfur, trace minerals, or vitamins

for

dried whey permeate.

The quality of dried whey from a nutritional

standpoint can vary depending on source of whey, drying

conditions, and age (Mahan, 1984). Two of the best indications

of the quality is color and ash content. A light, creamy

color is desirable. Whey that is overheated during drying

may have a brown color or dark flakes. A dark yellow

color is an indication that the whey has been stored

for a long period of time. These off-colors are indications

that the Milliard reaction may have occurred, meaning

that the ε-amino group of lysine becomes bound to carbohydrate,

rendering it unavailable to the animal. A high ash content

is also undersirable because it indicates that the whey

became acidic during storage and large amounts of sodium

hydroxide (a strong base) were added before drying to

raise the pH. This type of whey has excess salt and

can cause diarrhea in pigs.

Other Whey Products

Dried delactosed whey has had

a portion of the lactose removed during crystallization.

It still contains significant amounts of lactose (~54%)

and has slightly more protein (~18%) than normal dried

whey (Table 1).

Ultrafiltration of liquid whey separates most of

the protein fractions from the other fractions and results

in two products – whey permeate and whey protein concentrate.

Dried whey permeate has less than 4% protein but it

is quite high (~80%) in lactose (Table 1). A commercial

brand of dried whey permeate (Dairylac?80, International

Ingredient Corp., St. Louis, MO) is widely used in the

USA swine industry in pig feeds as a source of lactose.

It has nutritional properties that are similar to dried

whey (Cromwell et al., 1994). Whey protein concentrate

is considerably higher in protein than permeate, and

is used primarily in the human food industry.

Lactose

As stated previously, the predominant

carbohydrate in whey is lactose. This disaccharide sugar

consists of two monosaccharide sugar units, galactose

and glucose, joined in a β1,4-linkage. The bond between

the two sugar units must be cleaved so that the glucose

and galactose units can be absorbed (galactose is converted

to glucose in the liver following absorption), metabolized,

and utilized by animals. Young mammals, including pigs,

have an abundant supply of lactase in the small intestine,

so they are able to efficiently digest lactose and utilize

the two polysaccharide sugars for energy.

On the other hand, the enzymes needed

to degrade other disaccharides, sucrose (glucose-fructose,

α1,2-linkage), maltose (glucose-glucose, α1,4-linkage),

and isomaltose (glucose-glucose, α1,6-linkage) and more

complex carbohydrates such as starch are very low and

almost non-existant at birth. These digestive enzymes

are still relatively low at 2-3 weeks of age, so the

starch from cereal grains (mainly long chains of glucose)

is not as well utilized as after pigs reach 4-6 weeks

of age or older. Thus, a readily digestible carbohydrate

must be present in the diet for pigs weaned at an early

age in order for the pig to receive adequate energy.

Lactose fits this role ideally.

Nutritional Value

of Dried Whey and Lactose

One of the first studies to assess

the possible benefits of dried whey in diets for swine

was conducted in 1949 by Krider et al. at the University

of Illinois. These researchers found that as little

as 2 to 4% dried whey resulted in a 30% improvement

in growth rate of young pigs. However, they also reported

that higher levels of dried whey produced diarrhea in

their pigs.

Except for a few studies (Becker

et al., 1957; Danielson et al., 1960), relatively little

research was conducted with dried whey until several

decades later. In the early 1970’s we conducted studies

at the University of Kentucky to evaluate dried whey

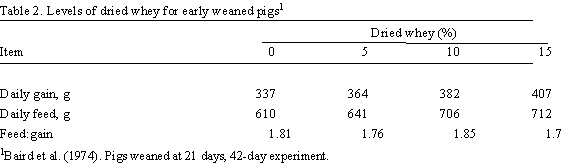

in diets for pigs weaned at 3 weeks of age. In one study,

we evaluated three levels of dried whey (5, 10, and

15%) added to corn-soybean meal-based diets for early

weaned pigs and found that growth rate and feed intake

increased linearly as level of dried whey was increased

in the diet (Baird et al., 1974; Table 2). In those

studies, we also found that the addition of lactose

at the same level as provided by dried whey produced

a similar growth rate and feed intake response as achieved

by feeding the dried whey.

|

Other studies at Ohio State University, Kansas State

University, and the University of Missouri have also demonstrated

the effectiveness of relatively high levels of dried whey

in diets for early weaned pigs. A study by Mahan (1992)

showed that pigs responded to levels of dried whey up

to 35% of the diet (Table 3). Similar results have been

shown in other studies (Graham et al., 1981; Tokach et

al., 1989; Nessmith et al., 1997). While some of the benefits

of whey have been attributed to the protein fractions

(Tokach et al., 1989), most of the research shows that

the benefits of whey are largely attributable to its lactose

fraction (Baird et al., 1974; Mahan, 1992). The

two performance traits in pigs that are affected most

by whey or lactose additions are feed intake and growth

rate. The improved growth response may be due to the

effect of these ingredients in stimulating feed intake.

In addition, lactose has been shown to maintain an enhanced

intestinal environment (Wolter et al., 2003).

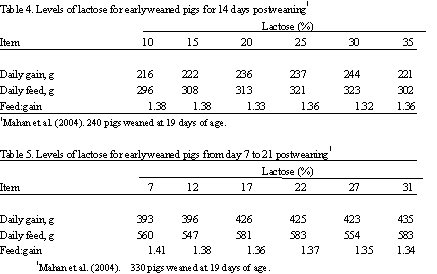

Questions often arise as to how

much lactose should be included in various phases during

the nursery period. A recent study (Mahan et al., 2004)

investigated this and found that pigs responded to high

levels of lactose in the diet during the initial 14

days post weaning (Table 4), and during days 7 to 21

postweaning (Table 5). From their studies, these researchers

recommended that 25-30% lactose be included during the

first week postweaning (to 7 kg body weight), and 20%

lactose for the subsequent 2 weeks (to 12.5 kg body

weight).

|

While it is clear from many studies

that most of the response to lactose occurs during the

first 2 to 3 weeks following weaning (i.e., starter

phases 1 and 2), there has been some question as to

whether the response to lactose continues during the

mid to late nursery period (phase 3). To more clearly

answer this question, a large study involving 1,320

pigs was conducted (Cromwell et al., 2005). The study

was conducted at the University of Kentucky, the University

of Missouri, and The Ohio State University.

Crossbred pigs were weaned at 15 to

20 days (6.2 kg initial weight) and allotted to five

dietary treatments. The pigs were penned in groups of

five pigs per pen at the Kentucky and Ohio stations

and in groups of 23 pigs per pen at the Missouri station.

There were eight replications per treatment at each

station for a total of 24 replications per treatment

in the study. Commercial style, temperature-controlled,

slotted-floor nursery buildings were used, and pens

were equipped with nursery-type self feeders and nipple

waterers. Diets and water were made available on an

ad libitum basis. Pigs were weighed and feed intake

was determined at weekly intervals.

The study consisted of four phases.

Phases 1 and 2 were each 1 week in length, phase 3 was

2 weeks, and phase 4 varied from 1 to 2 weeks in length.

Average pig weights at the end of the four phases were

7.5, 10.3, 17.9, and 25.3 kg, respectively. All pigs

received the same diet during the first two phases of

the study (Table 6). The two diets were calculated to

contain 20.0 and 15.0% lactose, respectively, and 1.60%

lysine (total).

During phase 3, five dietary levels of lactose (0,

2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0%) were fed (Table 6). These

diets were formulated to contain 1.56% lysine (total)

and 1.42% true ileal digestible lysine. In the phase

3 diets, Dairylac?80 was the source of lactose and was

substituted for an equal amount of corn. Levels of dicalcium

phosphate, ground limestone, and salt were adjusted

to maintain constant dietary levels of calcium, phosphorus,

and sodium. Also, levels of supplemental lysine, threonine,

and methionine were adjusted to maintain similar levels

of total lysine, threonine, and methionine + cystine

in the five diets. During phase 4, a common diet (mainly

corn and soybean meal with amino acids, but with no

lactose) containing 1.44% lysine (total) was fed to

all pigs. The diets were formulated to meet or exceed

NRC (1998) standards for amino acids, minerals, and

vitamins. Carbadox was included in all diets at 55 mg/kg.

In addition, zinc oxide and copper sulfate were included

in phase 1 and 2 diets at pharmacologic levels (2,150

mg zinc and 125 mg copper/kg) in phase 1 and 2 diets,

and copper was included at 250 mg/kg in the phase 3

and 4 diets.

Dairylac?80, a product of International

Ingredient Corp. (St. Louis, MO) was used as the source

of lactose in the experimental diets (phase 3). This

product is a granular, nonhygroscopic product produced

from sweet dried whey solubles. A single source of Dairylac?80

was used in the experiment. It analyzed 96% DM, 79.3%

lactose, 4.6% CP, 0.46% fat, 0.12% crude fiber, and

9.84% ash. Although not analyzed for amino acids or

minerals, Dairylac?80 typically contains 0.15% lysine,

0.52% Ca, 0.63% P, and 3.0% NaCl (product sheet, International

Ingredient Corp., St. Louis, MO).

The results of the study for the three

stations are presented in Table 7. In all instances,

daily gain and daily feed intake differed (P < 0.01)

among the three stations, and in most cases, so did

feed:gain. However, there was no evidence of a station

x treatment interaction for gain, feed intake, or feed:gain

during any of the test periods.

As expected, pig performance was not

affected (P = 0.10) during the initial 2-week experimental

period (phase 1 and phase 2) during which time all pigs

received a common diet. During the 2-week period of

phase 3 when the five levels of lactose were fed, both

daily gain and daily feed intake increased linearly

(P < 0.01) with increasing levels of lactose, but

feed:gain was not affected (P = 0.10). Although the

quadratic component was not significant, growth rate

and feed consumption appeared to reach a plateau at

the 7.5% level of lactose inclusion during phase 3 and

during phases 1, 2, and 3 combined.

During phase 4, when all pigs received

a common diet, pigs that had previously consumed the

phase 3 diet containing 10% lactose gained slower than

pigs in the other treatment groups (linear, P < 0.04).

Feed intake and feed:gain during phase 4 varied slightly,

but the differences among treatments were not significant

(P = 0.10). Over the entire 5 to 6-week study, growth

rate and feed intake were numerically greatest in pigs

that had been fed the 7.5% level of lactose during phase

3.

To determine whether the response

to lactose during phase 3 was maintained after pigs

were fed a common diet without lactose, the improvement

in growth rate of pigs fed the lactose diets compared

with the control diet was evaluated. The 7.5% level

of lactose resulted in 350 g of additional weight gain

per pig during phase 3 ([557 g/day – 532 g/day] x 14

days) and this was associated with 420 g of additional

feed consumed per pig during this period ([753 g/day

– 723 g/day] x 14 days). A determination of the additional

weight gain from the time that the additional lactose

was fed until the end of the study indicated that most

of the additional weight gain (294 g per pig) was maintained

throughout the study. The additional weight gain was

associated with an additional 409 g of feed consumed

per pig through the end of the study. Nearly all of

the additional feed consumed by this particular treatment

was during phase 3 of the study.

The results of this large collaborative

study clearly indicated that early weaned pigs continue

to respond to the feeding of lactose the third and fourth

week following weaning, and that this response is maintained

after the lactose source is removed from the diet. Furthermore,

the data suggest that 7.5% lactose is the most effective

level during the mid- to late nursery phase.

Summary

Numerous research studies conducted

during the past 30 years clearly demonstrate that the

inclusion of dried milk products, specifically those

originating from cheese production such as dried whey,

dried whey permeate or crystalline lactose in starter

diets for pigs stimulate feed intake and growth rate

during the postweaning period. These products are widely

used in the swine industry and their cost makes them

economically feasible to use in diets for early-weaned

pigs.

References

Baird, J., G.L. Cromwell, and

V.W. Hays. 1974. Effects of lactose and whey on performance

and diet digestibility by weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci.

39:179 (abstr.).

Becker, D.E., S.W. Terrill, A.H.

Jensen, and L.J. Hanson. 1957. High levels of dried

whey powder in the diet of swine. J. Anim. Sci. 16:404.

Cromwell, G.L., Hollis, G.R.,

and R.A. Easter. 1994. Assessment of DAIRYLAC 80TM,

spray- and roller-dried whey, and lactose in starter

diets for weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 72 (Suppl. 1):263

(abstr.).

Cromwell, G.L., G.L. Allee, and

D.C. Mahan. 2006. Assessment of lactose levels in Phase

3 nursery diets for young pigs. Abstract No. 289 of

the Midwestern Section, American Society of Animal Science,

Des Moines, IA, March 20-22, 2006.

Danielson, D.M., E.R. Peo, Jr.,

and D.B. Hudman. 1960. Ratios of dried skim milk and

dried whey for pig starter rations. J. Anim. Sci. 19:1055.

Graham, P. L., D. C. Mahan, and

R. G. Shields, Jr.. 1981. Effect of starter diet and

length of the feeding regime on perforamance and digestive

activity of 2-week old weaned pigs. J. Anim. Sci 53:299-301.

Halpin, K., R. Bradfield, F. Chen,

M. Trotter, and J. Sullivan. 2000. Creating a synergy

of simple sugars. Feed Management 55(5): 13-18.

Harper, W.J. 2000. Biological

properties of whey components – A review. American Dairy

Products Institute, Chicago, IL 54 pp.

Krider, J.L., D.E. Becker, L.V.

Curtin, and R.F. Van Poucke. 1949. Dried whey products

in drylot rations for weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 8:112-120.

Mahan, D.C. 1984. Dried whey is

not always dried whey. Ohio Swine Research and Industry

Report. Animal Science Series 84-1. pp. 30-33.

Mahan, D.C. 1992. Efficacy of

dried whey and its lactalbumin and lactose components

at two dietary lysine levels on postweaning pig performance

and nitrogen balance. J. Anim. Sci. 70:2182-2187.

Mahan, D.C., N.D. Fastinger, and

J.C. Peters. 2004. Effects of diet complexity and dietary

lactose levels during three starter phases on postweaning

pig performance. J. Anim. Sci. 82:2790-2797.

Nessmith, W. B., Jr., J. L. Nelssen,

M. D. Tokach, R. D. Goodband, J. R. Bergstrom, S. S.

Dritz, and B. T. Richert. 1997. Evaluation of the interrelationships

among lactose and protein. J. Anim. Sci. 75;3214-3221

NRC. 1998. Nutrient Requirements

of Swine, 10th edition. National Research Council, National

Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Tokach, M.D., J.L. Nelssen, and

G.L. Allee. 1989. Effect of protein and(or) carbohydrate

fractions of dried whey on performance and nutrient

digestibility of early weaned pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 67:1307-1312.

Wolter, B. F., M. Ellis,

B. P. Corrigan, J. M. DeDecker, S. E. Curtis, E. N.

Parr, and D. M. Webel. 2003. Impact of early postweaning

growth rate as affected by diet complexity and space

allocation on subsequent growth performance of pigs

in a wean-to-finish production system. J. Anim. Sci.

81:353-359.

|